This is the second installment in a series exploring how certain foods and drinks transcend mere sustenance to become unforgettable experiences. Each article delves into the personal and cultural narratives woven into a single drink or meal—revealing the memories, emotions, and moments that make them truly meaningful. From a great aunt’s brown bread recipe to a cocktail with cacao-infused absinthe, this series celebrates profound connection between taste and storytelling—and the flavors that linger long after the last bite or sip.

Community Breakfast At VFW Post 6859 – Portland

The first Sunday of the month 8-10:30 a.m.

“They have a waffle bar?” I asked my friend Professor A. “They do,” he replied, and that was how I found myself at VFW Post 6859 on Forest Avenue in Portland’s Woodford Corner neighborhood on the first Sunday of May.

Professor A also told me the breakfast was only $10 for adults with eggs cooked to order, bacon, sausage, home fries, and coffee. A Bloody Mary cocktail he said would run me $5 more. But, he had me at waffle bar. 🧇

I’m a tried-and-true breakfaster. I can eat breakfast any time of day or night. When I was a little girl, it was the stack of pancakes my dad made on weekend mornings or a trip to the neighborhood German pastry shop for fruity cheese Danishes. Adolescent summers at my aunt and uncle’s home in Arkansas was all about homemade biscuits slathered with peach jam, scrambled eggs, and a side of crispy bacon. College welcomed me in with breakfast burritos and the humble tuna melt. These days, adult me is all about that first jolt of caffeine followed by a thick slice of bread and marmalade.

Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) Post 6859

I pushed open the door and stepped into a long hallway lined with faux brown wood paneling—the kind that was really popular in the 1970s. Professor A and I passed the kitchen, where Jessica, an omelet wizard from Bayside American Café, was in her element. At the back of the building, we reached the bar area, which looked exactly like the kind of place where faithful regulars could slide onto a stool and feel right at home. No haze of smoke or Christmas lights here, but the past is present in the form of flags and plaques. Two women took our cash and handed us slips of paper to mark our orders— I went for a veggie omelet, and Professor A chose scrambled eggs with bacon and toast. They then led us into the banquet hall, where we claimed a spot at one of the foldout tables draped in white tablecloths surrounded by aluminum chairs. There were a couple dozen people already there at 8:30 a.m., but plenty of empty seats remained. The place would fill up over the next hour.

I made a beeline for the hot coffee from Willow’s Mobile Coffee Café. And that, my friends, is when I spotted Norm’s SOS Sausage & Gravy alongside a basket of buttermilk biscuits. I’ve had better biscuits, but that gravy was spot on. And I would know considering all the meals I’ve eaten across Appalachia and the American South.

It turns out Norm was a pretty big deal at this VFW. He was of the WWII vintage and a submarine guy. Back in the day crewmembers helped with all the chores. Norm was good at cooking and the sausage gravy was his thing. He passed on the recipe to his daughter Diana who also runs the waffle bar. *Want to see what a sub’s galley looked like and learn more about what crews ate check out this article from the San Francisco Maritime National Park Association.

**At the end of this Substack is a whole lot of love for sausage gravy.

Notes from a conversation:

Jared Sawyer, a VFW officer who organizes the monthly breakfasts, is a third-generation servicemember, following in the footsteps of his father and grandfather. He enlisted right after high school.

He has been a member of VFW Post 6859 since 2014. Jared explains that nonprofit organizations like the American Legion and the VFW were founded in the wake of the Spanish-American War. These groups support veterans through local, independently run posts across the U.S. Open to those who served in war zones—or their descendants—these spaces offer camaraderie, shared understanding, and a place where members can speak freely among peers.

Jared is a part-time breakfaster and a maple syrup purist—especially when it comes to homemade French toast made with sourdough bread from the Deering Oaks Park farmers’ market. When I mentioned I prefer the real stuff too, he told me guests are welcome to bring their own syrup to the breakfasts. Only imitation is available currently, which, given the price I find totally reasonable.

While the hall has been doing the breakfast for years, Jared and other hall leaders feel strongly they want to get the word out to the community that these meals—and the hall—are a space for everyone.

VFW halls often offset costs by renting out their space. When I told a friend about the breakfast, she said she’d once been to a graduation party there. It’s easy to see why—it’s a great venue: roomy, has parking, convenient location, and even more convenient is the rental price of $300 for five hours. You can also bring in your own caterer. I’m certainly considering it for something—Bread and Butter Catering take note! The only restrictions are you have to use their alcohol service, and while the capacity is 120, that would be a bit snug if everyone is seated.

Jared on his breakfast ritual:

Almost every night, Jared prepares his cold brew in a French press, using beans from 44 North that he grinds himself. He drinks coffee till about 10 a.m., a habit he picked up during his time in the military. “It helps me focus,” he says. He doesn’t touch sweetened beverages. “I just really enjoy coffee, and it helps me focus” he shares.

Jared on a breakfast dish that always feels like home:

No matter where he is, English muffins slathered with a lot of butter and Teddy Chunky peanut butter takes him back. “I love me some peanut butter,” he tells me. Jared grew up in Bangor and as a child was blessed to live next door to his grandparents. As a kid, he’d walk over in the mornings and that’s what they’d make him. Whenever he eats it, it reminds him of home and growing up.

Ideal breakfast:

Jared would want his wife with him for any of the following:

The bistro steak at American Bayside—Black Angus bistro steak, sundried tomato& garlic cream sauce, two poached eggs, Italian cheese blend.

The corned beef hash at Hot Suppa with their hashbrowns. Make that extra hashbrowns.

Dutch’s burrito— Omelette style egg with cheddar, hashbrowns, black beans, salsa, chimichurri, sour cream, and a flour tortilla.

A special breakfast memory

In the military, we had these shelf-stable bagged meals. You open it up, and everything is packed in there neatly. They used to have this breakfast one. There was one omelet thing that was awful. The other one was corned beef hash. I remember being in Korea, and you’d only one eat when doing maneuvers— you got what you got regardless of the time of day. Occasionally, you’d get a breakfast one. I like a good corned beef hash, and this was definitely not good, but it was a breakfast meal in a bagged, shelf stable military ration. It was a treat.

(On a military base) Lunches and dinners can be all over the place, but breakfast is consistent—sausage gravy is always available. Corned beef hash, oatmeal that’s been cooked in a big vat and sitting there so it’s solid-like. Bacon, sausage, ham, hard-boiled eggs, eggs cooked on the stove, and toast.

*What Jared is referring to are MREs—Meals, Ready to Eat, which require no cooking. Also jokingly known as ‘Meals Refused by Everyone,’ as they’re designed to be filling, if not exactly appetizing. Packaged in brown bags, MREs can last three to five years or up to nine months in 100-degree heat.

A bit about Biscuits and Gravy and the Appalachian landscape

I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to learn more about one of my favorite breakfast dishes—sausage gravy. It’s not loud or showy, not something one fantasizes about. It’s not even pretty. But spoon it over a biscuit, and it becomes something irresistible. I prefer it hot but will eat it at room temperature.

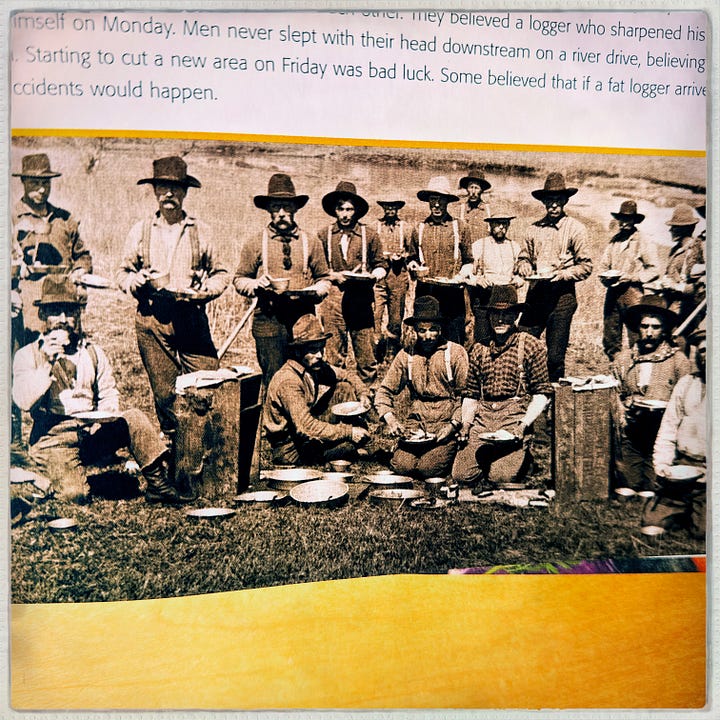

This hearty, countrified dish was a staple in Appalachian sawmills, logging camps, and coal mines as far back as the early 1800s. Workers faced grueling, dangerous jobs and needed sustenance that was cheap, filling, and easy to prepare—and biscuits and gravy fit the bill. It remains a staple of many communities today.

I’m genuinely interested in learning about place and people through the lens of food. So, I took to the World Wide Web, seeking out people with personal, multi-generational attachments to the dish.

Nancy Blackstone lives in Chicago with her college sweetheart, Kevin. I found her recipe for sausage gravy and reached out to her to see if there was a story behind it. She wrote back “My husband and his family do not know the origins of the biscuits and gravy recipe. Many of their family members worked in the Appalachian coal mines, and this hearty entree was often served with fresh eggs before sending the miners off to work.” Nancy raved about the recipe, which I’ll be trying soon.

Alex Fliegel is the director of Webster County’s Convention and Visitors Bureau. Webster county is 500 square miles of forest and timber companies own more than half of all private land. The last mine there closed in 2012. With loss of industry, the community has remained strong.

“I have lived in different places, but I wouldn’t want to be anywhere else but Webster County. Other than having the most serene landscape that surrounds you on every side, the people here is what makes it uniquely special to another place I’ve spent time in. This is community. This place is also my heritage. Though I’m born and raised in Cincinnati, my family roots are generations deep in this corner of Appalachia.

Alex says every restaurant in Webster County serves biscuits and gravy, and it’s just as common around the family dinner table. In fact, right after she emailed me about it, her mother—completely unaware—asked if she wanted sausage and gravy for dinner. It’s just that ingrained in everyday life.

If you ever find yourself in Webster County, make sure to eat at The Cookhouse at Holly River State Park. A plate of biscuits and gravy there will only set you back $5 plus tax and tip. “It’s food intentionally made by this community for this community,” Alex shares.

Here’s a description and recipe for Sawmill Gravy (Sausage Gravy or Soppy) from John Egerton’s book Southern Food: At Home on the Road in History. Even in lean times, a bit of meat, grease, flour, and water could make a satisfying gravy. That’s how Charles F. Bryan Jr. learned to make sawmill gravy growing up near McMinnville, Tennessee:

After cooking sausage in a black(cast-iron) skillet, leave behind the sediment or dregs and about 2 or 3 tablespoons of grease. Over medium heat, slowly sift in 3 tablespoons of flour, stirring constantly until the mixture is well-browned. Then pour in a cup of sweet milk (whole milk), add salt and pepper to taste, and continue stirring as the gravy cooks and thickens. (As an alternate method, the milk and flour can be blended in a shaker and poured into the skillet.) A piece or two of cooked sausage crumbled into the gravy adds substance as well as flavor. After it has simmered and blended for 2 or 3 minutes, pour the gravy into a separate bowl and serve it with biscuits, potatoes, or whatever. This recipe makes about 1 ½ cups.

Mark Sohn, an expert on Appalachian cooking writes in his book Appalachian Home Cooking: History, Culture, & Recipes:

Cooks prepare the gravy in the grease and drippings left from frying sausage. At breakfast, they split a biscuit and cover it with gravy, or serve the gravy beside sunnyside-up fried eggs, and mountaineers can mix the eggs with the gravy as they eat them. The gravy is also a wonderful accompaniment for sausage, pork chops, morels, fried potatoes, fried apples, or spooned over batter-fried meats such as chicken, liver, pork, and beef.

To keep the gravy white, don’t brown the flour, and use white ground pepper.

If you want to learn more about cooking in logging camps, Alex says look no further than a book called Tumult on the Mountain by Roy B. Clarkson. I’ve also found Maureen Fisher’s Nineteenth-Century Lumber Camp Cooking book fun and insightful (it’s a kid’s history/cookbook).